In foundries, metal fabrication shops, and maintenance teams, brazed diamond grinding tools have become a pragmatic answer to one persistent problem: achieving aggressive stock removal without sacrificing stability or burning through consumables. Among the most discussed formats, Brazed Diamond Grinding 100 stands out because its durability is not an abstract promise—it is a result of measurable decisions in diamond grade, braze metallurgy, and thermal control during manufacturing.

This article breaks down what actually improves service life, why the tool remains steady on materials such as gray cast iron and stainless steel, and what procurement and engineering teams can ask for when comparing suppliers.

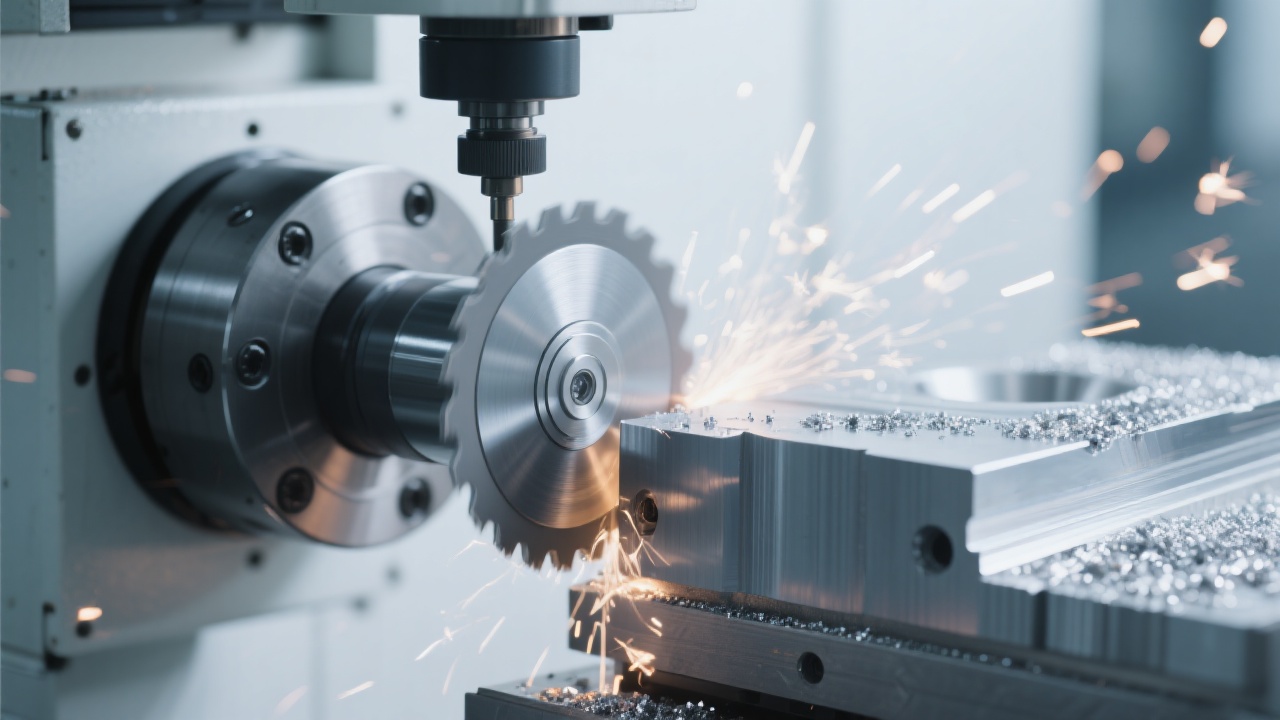

Traditional abrasive wheels depend on a resin or vitrified bond that gradually releases grains. That mechanism can be beneficial for self-sharpening, but in hard, heat-generating applications it often accelerates wear or glazing. In contrast, brazed diamond tools use a metallurgical bond to lock diamond particles to the tool body. When executed correctly, brazing creates high grain retention and exposes more cutting edges.

More protrusion + stronger retention means the diamonds cut rather than rub. Less rubbing generally equals lower heat, reduced micro-fracture, and more consistent performance over time—especially on hard inclusions, weld beads, and scale.

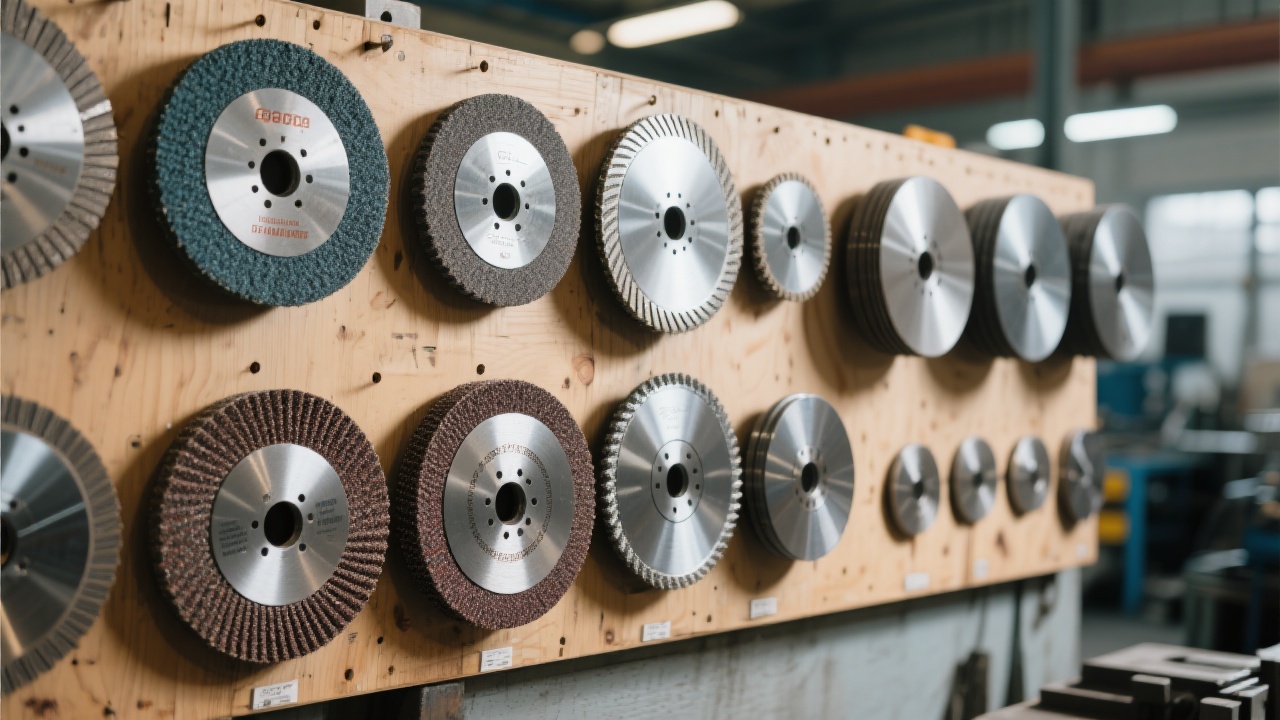

Tool life starts with the diamond itself. For rough grinding and long service, manufacturers typically use industrial synthetic diamond with stable crystal structure and controlled friability. A common, field-proven range for “100-class” performance is ~80/100 grit (or similar), balancing cutting speed with edge durability. Too fine may increase rubbing; too coarse may chip prematurely on shock loads.

Brazing is not just “gluing” diamond to metal—it is a chemical and metallurgical interaction. Nickel-based brazes are commonly used due to oxidation resistance and bond strength. From an engineering standpoint, a durable brazed tool shows: high wetting on diamond and substrate, uniform fillet formation, and minimal voids. These factors directly influence how well diamonds remain anchored under thermal cycling and impact.

The base steel (or alloy steel) matters because it determines stiffness, vibration response, and heat conduction away from the cutting zone. In production grinding, reduced vibration is often associated with fewer diamond pull-outs and more stable surface finish.

Buyers often hear “advanced brazing” without clarity. In practice, the best durability gains come from process control: temperature curve, atmosphere protection, diamond placement density, and post-braze inspection.

Many manufacturing engineers align on a simple rule: most “short-life” failures are retention failures, not diamond wear. That points directly to brazing quality—temperature stability, oxidation control, and the braze’s ability to wet and lock diamonds consistently across the working surface.

“Grinding 100” is often used in the market to indicate a performance class emphasizing aggressive removal with controlled scratch pattern. In successful implementations, the tool is designed to keep cutting edges exposed while managing heat and chip evacuation.

| Parameter | Common “100-class” reference | Why it matters for tool life |

|---|---|---|

| Diamond grit range | ~80/100 (application-dependent) | Balances cutting aggression and edge stability; reduces rubbing heat |

| Diamond protrusion | High protrusion, controlled density | More effective chip formation; fewer glazed areas; steadier cutting forces |

| Braze integrity | Low-void bond, uniform fillets | Prevents diamond pull-out under impact and thermal cycling |

| Body stiffness/runout | Tight tolerance assembly | Less vibration equals less micro-chipping and better diamond retention |

Note: The references above reflect typical market configurations and should be validated against your exact RPM, contact pressure, coolant strategy, and material condition (scale, casting skin, weld hardness).

Brazed diamond is not “one-size-fits-all,” but it performs exceptionally well when the job demands consistent cutting on abrasive or hard-to-grind surfaces. Practical results often depend on how the tool manages heat and loading.

Gray iron can be abrasive due to graphite and casting skin. Brazed diamond tools typically maintain a steady bite because the diamonds remain exposed longer. In workshop comparisons, users frequently report 2–4× longer usable life versus general-purpose abrasive wheels in deburring and surface leveling, especially when the operator avoids excessive dwell time on edges.

Stainless work-hardens and holds heat, which can punish weak bonds. A well-brazed diamond interface reduces early diamond shedding and can keep grinding action consistent. In controlled shop trials, switching from conventional abrasives to a quality brazed diamond grinding tool can reduce tool change frequency by ~30–60% in edge prep and weld dressing, depending on weld hardness and access.

In day-to-day production, operators rarely praise a tool for its best five minutes—they value what happens after the first hour. Feedback patterns for Brazed Diamond Grinding 100 commonly highlight: stable cutting feel, less sudden performance drop, and fewer interruptions from dressing or replacing consumables.

In maintenance teams, a recurring benefit is operational: longer life often means less tool inventory pressure and more predictable scheduling for shutdown windows—especially when grinding is a bottleneck step.

Tool life is a system outcome. Even a high-quality brazed tool can fail early if RPM, pressure, and heat are unmanaged. The following checklist is designed for procurement teams and supervisors who need repeatable results.

Healthy wear is gradual reduction in cutting aggressiveness with diamonds still present. Premature failure typically shows patchy bald areas (diamond pull-out), blueing from overheating, or vibration marks—signals to adjust RPM/pressure or re-check supplier brazing consistency.

Across industrial buyers, the conversation has shifted from “unit cost” to “cost per effective grind.” In many operations, a longer-lasting brazed diamond tool produces the strongest ROI not by being perfect in a lab, but by reducing interruptions, rework risk, and operator variability. As automation and takt-time pressure grow, predictable tool life is increasingly treated as a production parameter, not a nice-to-have.

Need a configuration that holds up on gray cast iron, stainless welds, or abrasive casting skin—without trial-and-error? Share your material, RPM, and process constraints and request a matched recommendation.

Get a Brazed Diamond Grinding 100 Tool-Life RecommendationTypical inputs: workpiece material (grade), hardness estimate, contact area, grinder RPM, dry/wet condition, target finish, and daily throughput.